Caspar Wolf: Lower Grindelwald Glacier, 1774

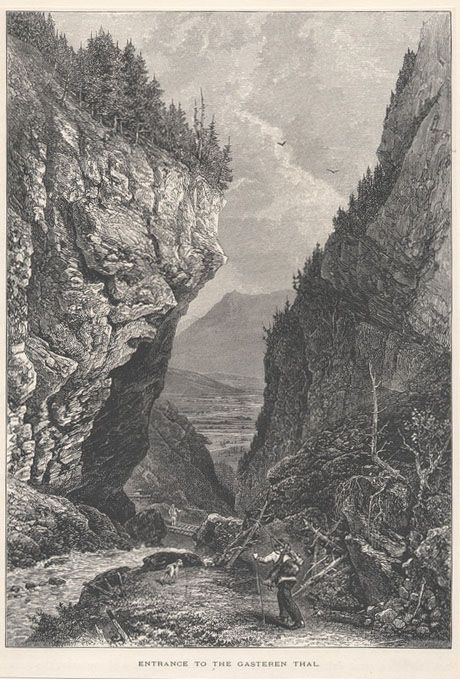

Gasterntal, Source: Kandertal Tourismus

The doctrine of the sublim

In the 18th century, popular perceptions of nature and the mountains began to change. The lofty and sublime became a symbol of freedom, and the very essence of that idea were the mountains. To Immanuel Kant, raw, untamed nature was an experience of the limits of freedom.

Enthralled by the sight of the Alps, Edmund Burke (1729-1797) wrote his Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of our Ideas of the Sublime and the Beautiful, in which he analyses the experience of greatness, the overwhelming, the sublime, and the pleasure we may derive from the horror it inspires: “The passion caused by the great and the sublime in nature is astonishment, and astonishment is that state of the soul in which all its motions are suspended, with some degree of horror.” Seen from a safe haven, the majestic peaks, craggy precipices and foaming waterfalls inspire wonder, awe and a delicious shudder of fear, rather than mortal dread. “Alpine tourism is basically the result of the popular appetite for horror” (Rodewald, 2011, p. 99) – a phenomenon that continues to this day.

British diplomat William Coxe (1747-1828) once said, “What a chaos of mountains are here heaped upon one another! A dreary, desolate, but sublime appearance: it looks like the ruins and wreck of a world.” Coxe borrowed a copy of Rousseau’s Julie – or the New Héloise and used it as a travel guide.

In the mid-18th century, landscape painters discovered the Swiss Alps, and they soon became a dominant motif in art and literature. Caspar Wolf is regarded as the first great painter of the Alps. He was the first to move the mountains into the centre of his pictures. Wolf was a passionate student of geology and tectonics and painted very naturalistic views of the Alps. In 1774, he produced his first panorama picture of the Alps, called “Grindelberg”. Waterfalls, wild mountain streams and dizzying gorges were among his favourite motifs.